My Blueprint for a Dynamic, Flourishing Vietnamese Film Industry

By Linh Duong

As a country with 4,000 years of complicated history, 54 ethnic groups, mixed culture and cuisines, rich geography ranging from mountains to large valleys to river deltas and, as is well-known, more than 3,000 km of coastline, Vietnam offers a rich source for great screen stories. However, to me, it often feels like the industry is not maximizing its capabilities.

I’ve been thinking for a while about how best the Vietnamese industry could realize its full potential – and here’s my nine point plan – blueprint – call it what you like. My belief is that this is entirely achievable if we all commit to the objectives and work closely together to accomplish it. This should be a joint effort from the Government, the Institute, the production companies, sales & distributors, and of course, the filmmakers themselves. Here we go:

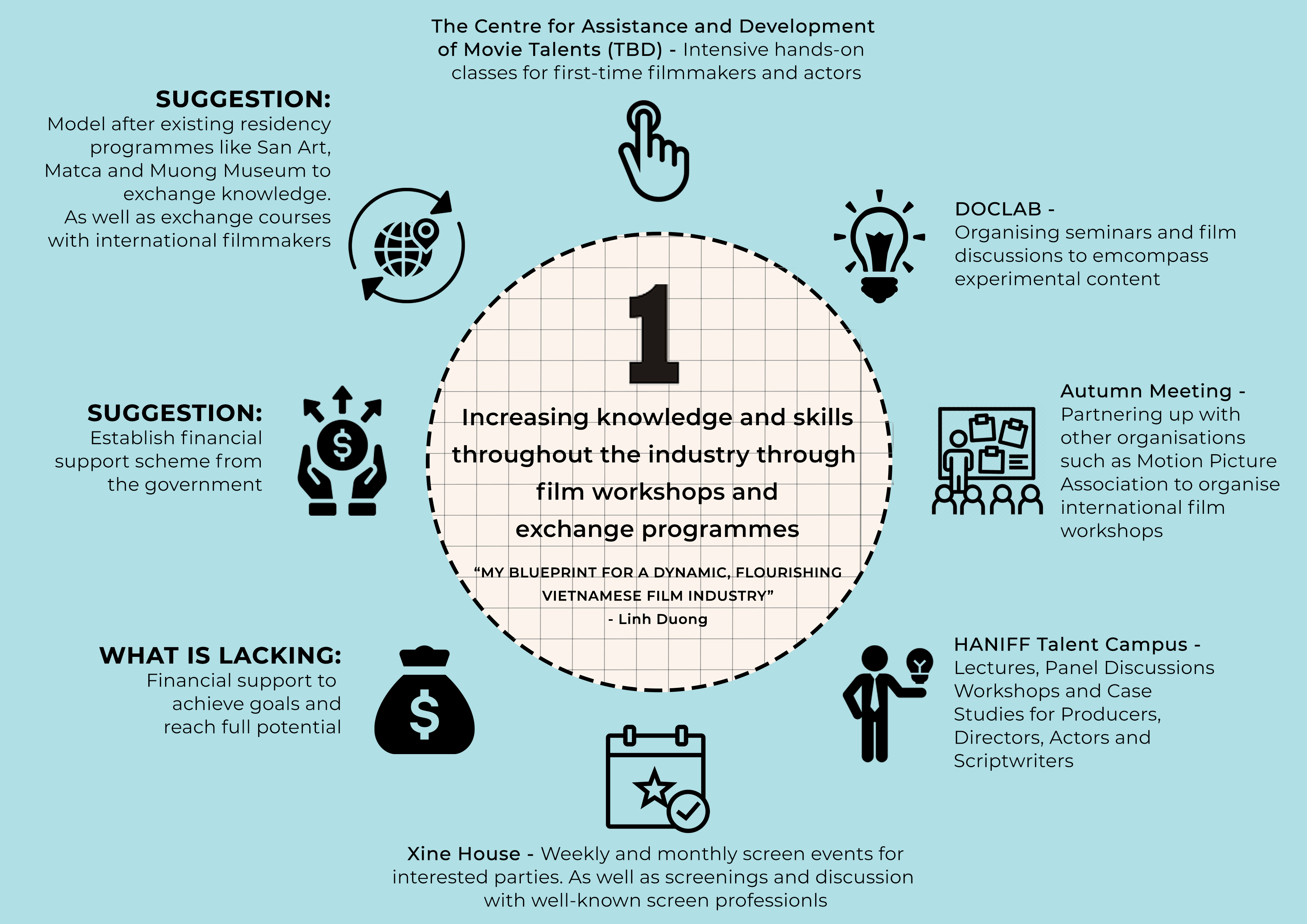

1. Increase knowledge and skills throughout the industry through film workshops, exchange courses:

First, let’s take a look at what’s out there:

- The longest-running cinema centers in Vietnam with regular activities to date are TPD (The Centre for Assistance and Development of Movie Talents) and DOCLAB, formed in 2002 and 2006 respectively. Both are managed by prominent Vietnamese filmmakers, namely Nguyen Hoang Phuong at TPD and Nguyen Trinh Thi at DOCLAB. TPD focuses on intensive, hands-on classes for first-time filmmakers and actors as young as secondary school students. DOCLAB started out as a documentary filmmaking lab, but has recently changed direction to encompass experimental content, all the while organizing seminars, film discussions and even offering venues for international talent exchange. Both are located in Hanoi.

- Arriving later, but on a larger scale is Autumn Meeting, an annual international film event held in Danang for the past 7 years. Founded by director Phan Dang Di, producer Tran Thi Bich Ngoc and screenwriter Nguyen My Dung, Autumn Meeting has gradually become home to not only Vietnamese, but international, filmmakers and actors, offering various workshops that cater to the needs of all film-related professionals. Participants are pre-selected through an application process, and more often than not they need to prove some level of knowledge in filmmaking. Besides in-depth seminars and talks with well-known Vietnamese and international filmmakers, the participants are also given a chance to pitch their commercial and art-house projects for a cash prize. Judges for art-house pitching are often programmers from prestigious festivals such as Venice, Cannes, Berlinale and Rotterdam; while commercial film pitches are considered by local commercial directors and producers. For a number of years, Autumn Meeting has partnered international film workshops co-hosted with the Motion Picture Association, focused on pitching skills and project development.

- Another notable film workshop is HANIFF Talent Campus, held under the banner of the Hanoi International Film Festival every two years. It offers a similar program with six intensive days of lectures, panel discussions, workshops and case studies for Producers, Directors, Actors and Scriptwriters.

- A new initiative called Xine House has been opened in Ho Chi Minh, offering weekly and monthly film events for not only filmmakers but also audiences who are interested in the local and international film scene. Their activities are practical and engaging, such as screenings and discussions with filmmakers or master classes and workshops with well-known film professionals. Xine House is also extremely active on social media, with a new post every day. Their content ranges from sharing technical knowledge, to film festival updates, to recommending good film titles or behind-the-scene of famous films.

Speaking of social media, there are quite a few independent Facebook groups in Vietnam that are founded by film enthusiasts, with regular posts reviewing classical films as well as recent films, such as Make Films; Not War or Viva Cinema.

As you can see, filmmakers and broadly well catered for when it comes to workshop activities. What is lacking, is perhaps a stablesource of financial support, as many of these organizations are struggling to find funding every year. Autumn Meeting, for example, is downsizing and moving from its annual venue at Danang City to Ho Chi Minh City. DOCLAB has to seek new space for their activities following declining sponsorship from the Goethe Institute. Xinehouse, Autumn Meeting and TPD have had to start charging fees for certain courses or seminars. I think this model is fair because the organizations can at least sustain themselves for the time being. But in order for them to reach their full potential and focus more on their goals rather than struggling to survive, perhaps it is time for the Cinema Department and the Ministry of Culture, Sport and Tourism to step in with financial support schemes for the arts, just like our neighboring countries in the region such as Singapore, Philippines, Malaysia, or setting the benchmark for support – South Korea?

With government support, we can also organize more residency programs that allow international filmmakers to stay in Vietnam and exchange their knowledge with local filmmakers, while sending our own filmmakers overseas. These could be modeled on existing residency exchange programs for artists, such as San Art, Matca and Muong Museum.

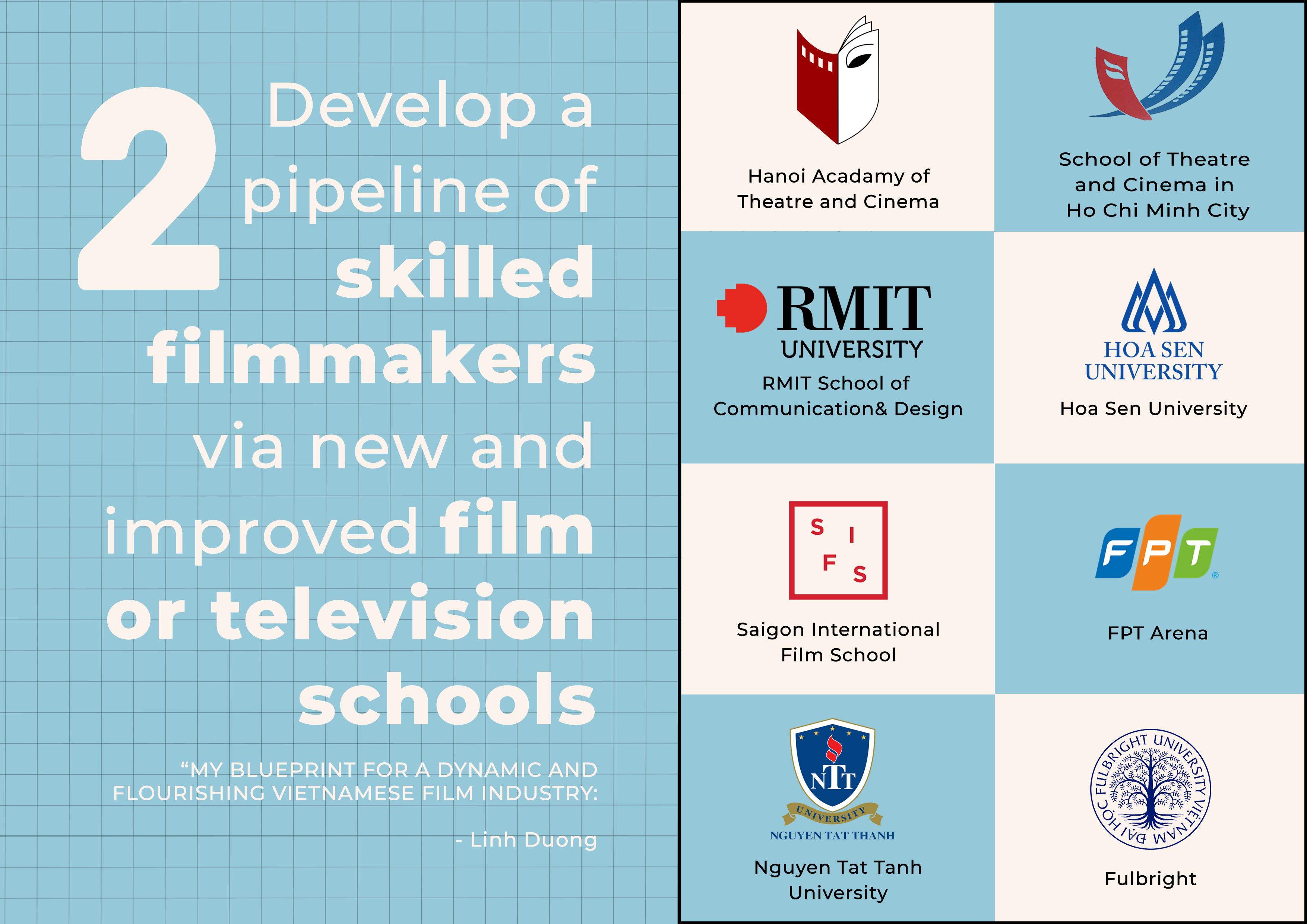

2. Develop a pipeline of skilled filmmakers via new and improved film/television schools:

The two government-funded film schools in Vietnam are the Hanoi Academy of Theatre and Cinema and the School of Theatre and Cinema in Ho Chi Minh City. In recent years, a number of new private schools providing film education such as RMIT School of Communication & Design, Hoa Sen University, Saigon International Film School, FPT Arena, Nguyen Tat Thanh University, and Fulbright University Vietnam, have appeared to service the sector.

While the government-funded film schools continue to follow a rather traditional, theory-heavy teaching method, the private schools offer much more up-to-date curriculum and practical skills building.

From my own observation of the offerings in both Vietnam and overseas, it is really important for film students to receive a good balance between theory and hands-on training, as well as soft skills that allow them to join the industry as soon as they graduate. It would be valuable for filmmakers to learn from both full-time professors and practising professionals who are actively creating new projects on a regular basis. Vietnamese filmmakers who have studied overseas are valuable to our growing industry, given that they can share international best practice.

I also suggest that it is time for the schools to consider offering essential film industry-related majors that are in high demand, such as production design, sound design, documentary filmmaking, film programming/curation and film business. There are many professionals working in these fields. A majority are self-taught through hands-on experience, but they lack the necessary theory and skills training. Take production design: We have far too many prop masters and possibly some good art directors who depend on the directors to make decisions for them. Unfortunately, very few production designers have the ability to develop a comprehensive creative concept that gives the film a unique look and feel. Even the set builders and prop masters are more often than not “workers” who simply execute what’s on the list, with very little aesthetic sensibility or knowledge of different materials.

The film industry in Vietnam is on the move. We are right on track to achieve great things, however, we’ll get there much faster once we successfully train our next generation of skilled filmmakers.

3. Provide Vietnamese filmmakers with clear content guidelines for developing stories that allow for creative expression:

The Cinema Code in Vietnam provides content guidelines and age ratings for film and television content. All Vietnamese productions or co-productions with foreign companies are required to submit their project at script stage to receive permission to begin production. During this stage, the Censorship Board can ask the filmmakers to alter or remove sections from their films that they feel not suitable for a Vietnamese audience. However, the guidelines for what content is considered “unsuitable”, and what is not, is still widely open to interpretation, so every filmmaker submitting their project to the Board is unable to anticipate the outcome. Filmmakers often learn via word-of-mouth from their colleagues the sort of content they should avoid in their scripts, and will self-censoring in advance of submitting their project for approval.

Once the edit is completed, a film has to be submitted once again for rating. Vietnam’s Censorship Board established a new rating system in 2017, which comprises four categories – P, C13, C16 and C18. Similarly, the standard for rating a film under each category is rather vague and not consistent. A full explanation and transparency of how films are rated does not appear to be easily accessible to the public – two hours searching online resulted in a brief, half an A4-page list of generic information. On the official website of Vietnam Cinema Department I managed to find a couple of Official Circulars that announce some law changes over time, but no sign of the full outline of rating categorization. This does not make it easy for both film distribution and sales companies. It may result in additional production costs for editing, perhaps the butchering of an entire plot, or assigning an incorrect rating due to unclear and inconsistent application of content ratings guidelines, impacting how the film plays to its intended targeted audience or even shortening the theatrical release.

By comparison, two simple clicks on the official website of Singapore’s Infocomm Media Development Authority (IMDA) took me to an 18-page guideline that is super detailed, even to the point of explaining which individual profanity can’t be used for each rating. They also include a glossary that clearly explain all of the terms applied. This level of accessibility and transparency would save both the filmmakers and the Censorship Board a lot of time, especially in the coming years as Vietnamese cinema is anticipated to grow exponentially. We can learn from them.

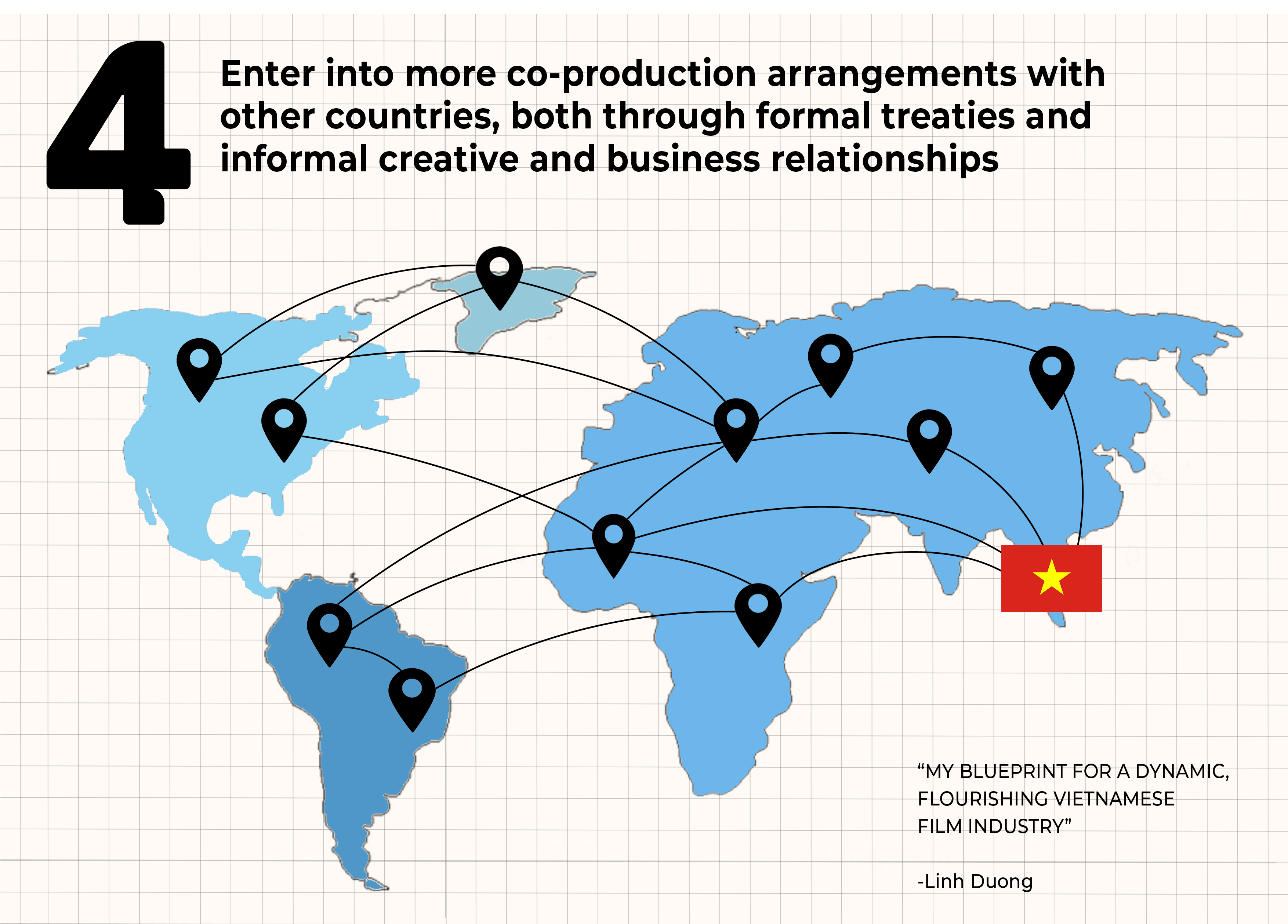

4. Enter into more co-production arrangements with other countries, both through formal treaties and informal creative and business relationships:

International film co-production has been around for decades, but in recent years the concept has become a global trend with great benefits for all parties involved. Not only do co-productions open up opportunities for funding resources, they also allow an exchange of knowledge and skillsets between international filmmakers, and boost wider distribution of the end product.

In Vietnam, many independent films have been funded by engaging one or more co-producers from largely European countries such as France and Germany – think The Buffalo Boy; Bi, Don’t Be Afraid!; Flapping in the Middle of Nowhere for example. South Korea’s CJ Entertainment has been the most active partner on commercial co-production projects since the mid-2000s.

However, Vietnam has yet to issue formal treaties for co-production with other countries. By comparison, Canada has close to 60 coproduction treaties, followed by France with over 55 treaties. As attractive as it sounds, co-production is a challenging process with lengthy paperwork and various risks involved. It’s crucial therefore, to provide a legal framework that safeguards our own filmmakers. Coproduction treaties will benefit all parties involved by providing clear guidelines to access financing resources and ensure a fair share of the rights and revenues among co-producers.

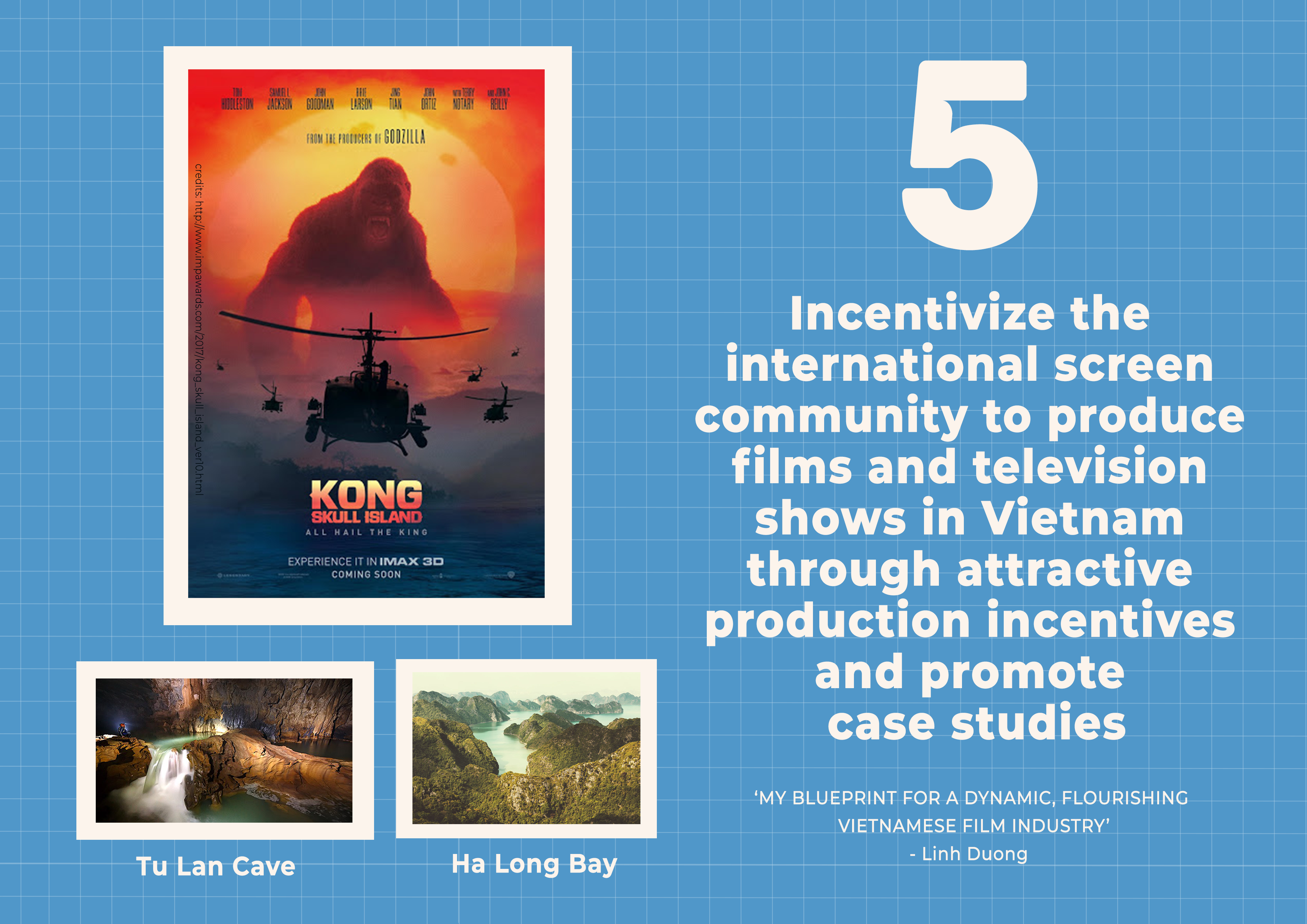

5. Incentivize the international screen community to produce films and television show in Vietnam through attractive production incentives, and promote case studies:

Vietnam has always been an attractive destination for international film producers, even long before the production of Kong: Skull Island in Ha Long Bay, Quang Ninh, Ho Yên Phú, Phong Nha, and Tân Hoá, Quang Binh, in 2015-16. Now, as the spotlight turns on Southeast Asia, Vietnam is one of a number of countries being scouted for high profile film and television productions.

However, we are losing out to our neighbour competitors such as Thailand, Cambodia, Singapore and Malaysia simply because our offer does not stack up:

-

-

- We are not in a position to offer formal agreements through co-production treaties as mentioned above;

- We cannot offer a formal legal framework that accommodates foreign film productions;

- We offer little in the way of professional production and crew services;

- We make it difficult to enter and shoot in Vietnam because of our complicated and lengthy permit application process.

-

But perhaps, most problematic of all, producers discount Vietnam at the first hurdle because we do not make it financially attractive for them include Vietnam in their budget calculations. Quite simply the numbers don’t add up.

Let me illustrate this via my personal experience. Recently I took a walk through the European Film Market at the Berlin International Film Festival. Glaring down at me in big bold signs, on country film stalls to my left and right, and again mirrored in a variety of booklets at my fingertips, were propositions I just could not ignore: “30% Cash Rebate!”: “20-40% Refund on Expenses!”; or perhaps the most competitive offering out there, an astonishing “47% Film Tax Rebate” from Fiji.

There are a number of countries we could look to for establishing a proven, sophisticated, economically responsible production incentive – either Australia or NZ would be a good place to start.

The production of Kong: Skull Island a few years ago was a missed opportunity to closely monitor the economic activity and local employment stimulated by the project. This data would have proved invaluable to informing the development of a production incentive in Vietnam. One option we have is to mirror the current experiment by the Japanese Government, which is trailing a new production incentive for two major international productions – Snake Eyes, from Paramount Pictures, and Detective Chinatown 3, from Wanda Pictures. The Japanese Film Commission is capturing all of the economic data to illustrate how those productions provide jobs, bring investment to those towns hosting the production, and in the longer term, build an entire film tourist economy for the country. In April, they provided funding for two more international films. I’d like to see the Vietnamese Government try this. It’s low risk, with plenty of upside.

6. Incentivize and open up the market to encourage more cinema growth with international investment:

A successful example of international investment in Vietnam is the CJ Group from South Korea. Since 2005, when they became known through a popular TV series, CJ has become a well-liked, highly-recognizable brand. CJ CGV quickly became the leading cinema provider, offering 87 cinema locations and growing, while its sister investor-distributor company, CJ Entertainment, has got way ahead of the competition, enjoying a string of successful co-productions with Vietnamese partners.

However, CJ CGV’s arrival and rapid growth has created a number of challenges for local production companies and distributors. CJ CGV now claims 47 percent of the market share, while another South Korean company, LOTTE, has quickly moved to claim a further 30 percent, leaving two Vietnamese exhibitors with a very small piece of the pie.

This example shows that while actively opening up the market, the Government also needs to come up with ways to incentivize more investment in the sector from local and international business. Meanwhile, many films produced by CJ Entertainment are remakes of successful Korean films. While it’s good to have high quality films being localized and scoring big at the box office, it’s also unhealthy for the creative industry if we can’t find a balance. Vietnam is such a big country oozing with talent and stories to tell. What we need right now is a new wave of original, local content. How do we achieve that?

Let’s take a look at our neighbor Indonesia. Ten years ago, the country produced only a handful of films per year. As of 2019, they are ratling off 150+ titles annually. Indonesia entered a new golden age of cinema following President Joko Widodo’s 2015 removal of the film industry from the Negative Investment List. As a result, a flood of foreign money flowed into Indonesia. Hundreds of new cinema screens opened up for business, right across the Indonesian archipelago. President Widodo created the Indonesian Creative Industry Council to fund creative projects, support filmmakers and organize workshops. The impact on filmmakers was just stunning. Young talents got down to business producing new movies for both local and global markets. Even Hollywood studios have come knocking for collaborations and co-productions.

This is just one example of how much an industry can grow with the determined support of the Government. I believe we need just one push to jump-start an entire industry such as tax incentives to attract international productions to shoot in Vietnam and boost tourism. But that push needs to come from the Government.

7. Engage deeply with the international ecosystem of film festivals and awards shows, ensuring that Vietnamese films and television shows are profiled and recognized on a global stage; and promote Vietnamese content at leading film and TV markets:

International film festival and film markets are extremely useful when it comes to selling and distributing local films and promoting our country as an ideal shooting location. As seen in the photo attached – many countries promote their own catalogue of films produced in recent years, highlighting their production status and festival screenings, as well as making available contact books for local production companies. The most advanced countries present their films and filmmakers in large, cleverly-designed booths, decorated with poster art and sophisticated marketing materials and trailers on large flat screens – and of course whatever production incentive they are offering at the time. It is also clear that the Government departments and agencies responsible for the film industry are closely aligned and working together towards the same goal. Take a look at the Korean booth next time you go through a film market – you’ll see what I mean.

I’m happy that Vietnamese filmmakers are now representated by an organization whose name might one day appear on one of those booths. The formation of the Vietnam Film Development Association (VFDA) has proven to be a well-received initiative that goes some way to achieving some of the objectives proposed in this article. Throughout 2019, the VFDA has been present at a number of international film festivals, carrying the torch for Vietnam’s filmmakers and promoting our latest films.

I had the opportunity to attend one of their festival talks at last year’s Busan International Film Festival. Dr. Ngo Phuong Lan, Chairwoman of VFDA and former General Director of the Cinema Department, was there to announce the formation of VFDA, conceived to promote Vietnam’s recently made films and introduce our attractive shooting locations. However their one-hour talk was staged at quite a distance from the main Market venue, and could not really compete with those countries showcasing their wares at a booth in the exhibition with representatives actively engaging visitors throughout the market. Having said that, I’m really glad that the effort was made, and I hope that over time, the VFDA can play an important role in harnessing all of the positive creative output of Vietnam’s filmmakers, and represent our industry on the international stage.

Perhaps when it comes to festival visibility, we could learn one thing or two from our neighbour Philippines. Not only do they have a physical booth at every major film market, they also organise a Philippines’ Night – represented by personnel from the Film Development Council of the Philippines, the Embassy of the Philippines, as well as prominent filmmakers and movie stars attending the festival. They even use the occasion to promote local cuisines, beverages, and of course music and lots of fun for attendees. I believe they are able to make this happen thanks to the tremendous support from not only the film-related ministries, but also the Government as a whole. This ‘togetherness’ sends out a great vibe about the country’s film industry, and I believe helps a lot in attracting potential investors or collaborators.

8. Ensure that creative rights are protected and IP can be fully realized by strong copyright laws:

Vietnam has a framework for protecting intellectual property rights, but in many cases the artists don’t realise the importance of protecting their work at the very early stages of the creative process. In order to ensure that parties involved in filmmaking enjoy the fruits of their labour, it is extremely important that performers, directors and producers learn as much as possible about intellectual property law and seek professional legal advice on the assignment and licensing of rights.

Another problem with IP rights violation in Vietnam includes piracy. Many Vietnamese filmmakers are victims of piracy websites that upload their films online, sometimes less than one day after opening in the cinema – films such as Em Chua 18, Lo To, Co Ba Sai Gon, Nguoi Vo Ba, and many others. The rise of social media presents another problem when audience members start livestreaming the entire film on Facebook or Tiktok, as happened with Gai Gia Lam Chieu 3. Those attention-seeking individuals even make use of the Story function on Facebook and Instagram, knowing that the content will disappear after 24 hours and will then be limited only to friends and family, hence eliminating the fear of getting caught.

The violators usually do it for personal benefit or due to lack of basic knowledge of IP rights. However, what we need from the Government are enforcement measures that include an appropriate punishment that deters would-be pirates. At the same time, they could apply robust enforcement measures to take down major piracy website operations operating in Vietnam. These changes would make a huge impact on filmmakers, perhaps proving the difference between the chance of a lifetime career in the industry, versus having to give up their creative dreams for good

9. Work together and create dialogue!

Last but not least, let’s work together to achieve this. Lord Puttnam, the British producer well-known for such films as Chariots of Fire, The Killing Fields and Local Hero, administrator of many film and television organizations – and a guest speaker at a Hanoi film masterclass, has always encouraged those in a film industry to pull in the same direction, find shared goals, and not fight amongst one another.

I’m going to talk about my Filipino friends again, because I really admire how close-knit they are whenever we meet. For example, I was sitting in a café in Winterthur with four Filipino filmmakers (yes, there are always many of them with different projects at a single film festival). Out of curiosity, I asked why they all seemed like best friends, or for that matter, why all Filipino filmmakers seem like best friends? The answer was simple but mind-blowing: “Well, I wrote his script, he edited my film, she produced another, and he’s also shooting it!” They all work on each other’s films, literally! I guess that’s how relationships are built, knowledge is shared, and how everyone managed to push one another to be better. Singapore’s Thirteen Little Pictures and Cambodia’s Anti-Archive are also two wonderful examples of how filmmakers can achieve great things when working together. In Vietnam, many filmmakers have also found their life-long film partners through cinema centers and workshops like Autumn Meeting, TPD, or DOCLAB.

I believe these close relationships and support doesn’t simply stop at film production. They offer something powerful in times of crisis. During the coronavirus pandemic, where those in the creative community are among those suffering the most, a group of Filipino filmmakers started Lockdown Cinema Club, an initiative to raise funds and support members of the freelance filmmaking community who most needed help. To date, the program has supported over a thousand workers.

Why did I mention dialogue? Because that’s how the Singapore and Philippines’ governments are assisting those filmmakers affected by COVID-19. Singapore’s IMDA sent all freelance art practitioners including filmmakers an in-depth survey asking by how much their monthly income and working hours have been reduced since the outbreak. Everyone involved was provided with an equitable amount sent immediately via Paynow. The Film Development Council of Philippines (FDCP) has been conducting consultation meetings with representatives from various film-related sectors to produce a guideline that local filmmakers can follow for production shoots as soon as the pandemic is over. I believe these efforts are much appreciated by filmmakers, because it clearly shows that the authorities listen and appreciate the needs of their filmmakers.

At the end of the day, I believe we are all brought together by the love for cinema. If you want to go fast, go alone. If you want to go far, go together. As cheesy as it sounds, I know for a fact that film is not something one can do without help from others. Collectively, we can make the Vietnam film industry to be all it can be – and that, I believe, is a lot.

BIOGRAPHY

Linh Duong is a Vietnamese independent filmmaker who is extremely fascinated with sad, angsty and naggy middle-aged women. She has just completed a series of shorts that tackle this topic with a rather quirky sense of humor. Her films have been competing and winning award at various festivals around the world.

Linh previously attended Berlinale Talents in 2020, Asian Film Academy in 2016, Locarno Summer Academy, Bucheon Fantastic Film School in 2015 and also Autumn Meeting almost every year since 2015. She is developing her first feature, Don’t cry, butterflies, which recently won Moulin D’andé-CECI Award at Locarno Open Doors 2019. She won the 2019 Script to Screen Film Workshop hosted by the Motion Picture Association, American Centre HCMC, and Autumn Meeting.